Reflecting on The Geopolitical, Historical, Security, and Personal Implications of 9/11

On September 11, 2001, Kara Rhoads, a retired FBI agent, dodged chaos as she attempted to report to work.

She parked a block from the South Tower after a plane fatally damaged it and witnessed people jumping from the building just before it collapsed. Her car filled with debris, nearly suffocating her, but she made it out alive. The next day, she was assigned to a task force which worked 24 hours on, 24 hours off, searching the rubble for bodies and personal belongings.

“To this day, I still feel like I’m missing something, and I think it reverts back to then,” Rhoads said. “Did I miss a body part and now that family doesn’t have closure because I missed it? This is the burden that first responders hold.”

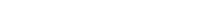

Rhoads was one of four panelists invited by the Office of Veterans and Military Services to discuss the geopolitical, historical, security, and personal implications of 9/11. Other panelists included SFC Victor Arocho ’21, United States Army National Guard; Ahmet Yayla, Ph.D., director of the Center for Homeland Security; and Andrew Essig, Ph.D., professor, chair of the social sciences department, and chair of the political science major.

Arocho described his own harrowing experiences following 9/11. When he enlisted in the military at age 17, he had no idea that less than a year later he'd be headed off to war. From that moment on, his life was never the same. He lost friends during the war and said that those who survived still suffer because of traumatic experiences overseas. After recent events in Afghanistan, some question whether their service mattered.

The implications of 9/11 and recent events in Afghanistan are complex, but Yayla and Essig provided context.

Essig detailed three historical components that lead up to 9/11: American foreign policy in the Middle East, regimes in the Middle East, and globalization. He discussed how the U.S. initially supported some of the oppressive dictatorships in the Middle East out of fear that something worse could happen if they didn’t. He also said that most terrorists often radicalize after visiting developed countries because they feel humiliated and disappointed by what’s going on at home.

Like Essig, Yayla urged the importance of understanding the ideologies driving terrorism. He reiterated the U.S.' role in supporting oppressive regimes and indicated why the U.S.’ global war on terrorism may not have worked.

“Is a sledgehammer the best tool when we are fixing something?” Yayla asked. “We used our military to fix this problem. When we use the military, people die because they’re trained for war…what happens then when a family member of yours dies, regardless of the reason? You become emotional…The more we kill, the more we imprison, the more we harm, regardless of who they were….their friends become enemies to the U.S.”

Although the implications of 9/11 and current events remain difficult to process, neither Arocho nor Rhoads regrets their role.

“People ask me, ‘If you knew then what you know now, would you have still gone in?’” said Rhoads. “I say yes. That is my job. That’s what I do. That’s what first responders do. They rush in when everyone else runs out.”

Arocho was grateful to have served his country and said, “The military isn’t for everyone…but I’m privileged and I’m honored to have people at DeSales that took care of me and to be able to have shared my experience with each and every one of you.”