Author Sarah Gray Discusses Loss of Newborn Son, His Contributions to Medical Research

Sarah Gray was only a few months pregnant when she and her husband received the devastating news. Doctors had diagnosed one of their twin sons, Thomas, with the fatal birth defect anencephaly.

There was a good chance Thomas wouldn't be born alive. Even if he were, he wouldn't live long. Thomas died just a few short days after his birth. But thanks to his parents, his life continues to impact others.

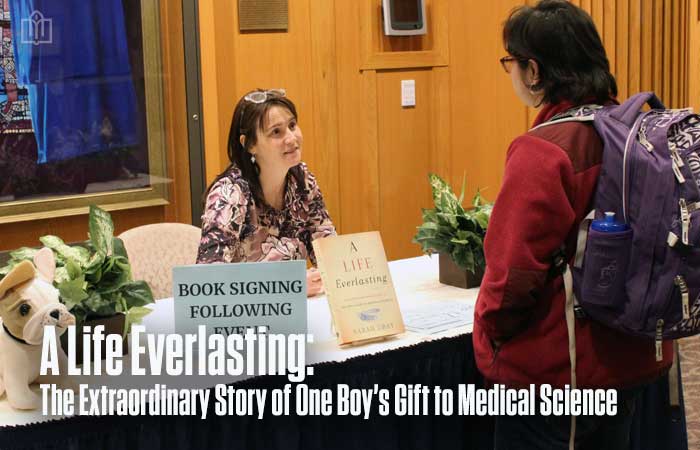

Sarah Gray, author of A Life Everlasting: The Extraordinary Story of One Boy's Gift to Medical Science, recently shared her family's story of heartbreak and hope with the DeSales community.

She was pregnant with twins in September 2009 when she and her husband were given the diagnosis. One baby was healthy but the other had anencephaly, which prevents the normal development of the brain and bones of the skull.

"I was stunned. I had so many questions. I just felt dizzy," Gray told the crowd.

She decided she wanted Thomas' short life and death to have meaning, so she asked her doctor if she'd be able to donate his organs and tissue for research.

Gray gave birth to Thomas and Callum on March 23. Both were born alive.

"Thomas sort of surprised us," she said. "He was cuddly; he was affectionate. He was missing the top part of his skull. Aside from that, he acted pretty normal."

But Thomas suffered a seizure that same day. He had two more the following day. The Grays took both their boys home, where Thomas passed away a few days later.

"I felt that this was a good way to die—surrounded by your family," Gray said. "I felt pretty proud of the way he left this world."

The next day, Gray got a call that the donation recovery had been a success. Thomas' liver was sent to a biotech firm in North Carolina, his corneas went to Harvard University, his retinas to the University of Pennsylvania, and his cord blood went to Duke University.

After that, Gray became curious. She wanted to see for herself where Thomas' donations went and how they were impacting medical research. She contacted Harvard and visited the lab and Dr. James Zieske.

Zieske told Gray that infant corneas are so rare that his lab only requests 10 pairs a year. His research centered on using umbilical cord blood on a cornea to see if it would grow. The hope is that one day, stem cell eye drops could replace cornea transplants.

"It's like my son's final resting place," Gray said. "The history that is behind this place, my family is now part of this history."

Gray also visited Duke, Cytonet, and the University of Pennsylvania—where one researcher had been waiting six years for a sample of tissue like the one Thomas donated. She also got to meet the woman who held Thomas' liver, and learned that it was used in a study to determine the best temperature to freeze infant liver cells.

"The way I see things now is that Thomas got into Duke, Penn, and Harvard. He has a job. He is a productive member of our society. He has co-workers and colleagues who need him. He's relevant. As a mom, you like to brag about your kids. This is a way that I can still brag about him even though he's not here."